In 2008 a new group of human ancestors – the Denisovans, were defined on the basis of a single finger knuckle (phalanx) bone discovered in Denisova cave in the Altai mountains of Siberia. A molar tooth, found at Denisova cave earlier (in 2000) was determined to be of the same group. Since then extensive work in the region has identified that at the time (about 40,000 years ago), modern humans (ancestors of all people alive today), Neanderthals (to whom we’re also related) and Denisovans shared this environment. Since then, more fossils have been found at the cave and identified as being Denisovans. Their ancestry has also been extended back for many hundreds of thousands of years. More significant than the number of fossil bones, however, is the contribution to our genetic understanding of our ancestry. The DNA sequenced from the Denisovan fossils has been compared to DNA from archaic and modern humans, as well as Neanderthals, allowing us to build up an understanding of the connections between our own ancestors and others in our lineage. The more we understand of this history written in our cells, the more it becomes apparent that we are the result of a complex, interwoven tapestry played out on an enormous framework across the planet.

About 1.9 million years ago, Homo erectus hominins left Africa and began spreading across the world. Homo erectus, whilst enormously successful and persisting in some areas until quite late in the biological sequence (perhaps as late as 50,000 years ago), also seems to have been the origin of several hominin lineages, including our own. The genetic evidence is crucial as it can reveal patterns and developments over time, without being hampered by gaps in the fossil record. For example, we have not found Denisovan fossils anywhere except at Denisova cave in Siberia, however, we can see their genetic influence in populations in other areas. Most intriguing of all was the discovery at Denisova cave in 2014 (published in August this year) of a long bone fragment of a woman, now known as “Denny”, who had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father.

The current understanding is that about 25 920 generations ago (geneticists work in generations, and assume 30 years per generation, on average) there was a divergence from the Homo erectus population of an archaic species (perhaps the fossils designated Homo heidelbergensis and similar). The ancestors of modern humans were part of this divergence. Perhaps only 300 generations later, Neanderthals and Denisovans formed two lineages out of the remaining archaic population. However, this did not result in 3 perfectly distinct lineages.

Denny’s mother was a Neanderthal from the Altai region, however, genetically she was more closely related to a fossil found in Croatia than to a Neanderthal fossil found in Denisova cave and dated 30,000 years earlier! The Neanderthals found at Altai also contain genetic markers showing links to early modern humans from a later time period than the original divergence. The Denisovan DNA also suggests that there is another (so far unknown) hominin species which had had an earlier separation from the Homo erectus line, which contributed 8% of Denisovan DNA. The Denisovan genome also contains a 17% overlap with the local Altai Neanderthals, suggesting a significant level of exchange of genetic material (interbreeding).

Modern humans who do not have solely African ancestry have between 1 and 4% Neanderthal DNA. Melanesian populations have between 4 and 6% (or possibly even higher) Denisovan DNA. Australian Aboriginals and some groups scattered across South East Asia also have Denisovan genetic markers, suggesting that Denisovan ancestry spread into South East Asia at some point. Small amounts (about 0.2%) of Denisovan DNA are also found in modern Asian and American First Nations people populations. Some modern East Asian populations (including Han Chinese and Japanese) show evidence of two groups of Denisovan DNA – one similar to the South East Asian populations and a second one more similar to the population in the Altai region of Siberia, suggesting two periods of genetic exchange. There is also some suggestion of genetic mixture between Denisovans and people in west Asia.

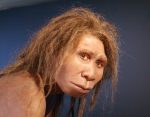

It would seem that Denisovan DNA may be expressed as dark skin, brown hair and brown eyes, as well as a gene assisting with low oxygen adaptation at high altitudes, found in modern Tibetan populations. This can be compared with the Neanderthals genes which entered the European modern human populations and express as light skin, red hair and freckles. What is abundantly clear is that our ancestry throughout history and prehistory is not so much a tree as a complex, interwoven web. As can be seen in any modern population we all have a wide range of different characteristics that reflect our broad and diverse genetic history. We can also see that all humans, our ancestors and relatives throughout time have always moved widely across the world and formed families together with people in different areas. We are indeed a global species.

So how do we know if we have Neanderthals genes? Neanderthal genes have some physical characteristics, but also other attributes that we can’t see. In terms of physical characteristics,

So how do we know if we have Neanderthals genes? Neanderthal genes have some physical characteristics, but also other attributes that we can’t see. In terms of physical characteristics,

Aunt Madge's Suitcase was a really fun activity! The children were really interested in all the places she travelled to,…

Indi Alford, Teacher