It is fairly well known that many Europeans in the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries did not follow the same routines of hygiene as we do today. There are anecdotal and historical accounts of people being dirty, smelly and generally unhealthy. This was particularly true of the poorer sections of society. The epithet “those dirty peasants” was meant quite literally. We often think that the lack of hygiene was related to the poverty and that people were too poor to be able to wash regularly – either themselves or their clothes. Being poor was certainly part of the equation, but in a more complex way than expected, as it was in fact government policy and taxes in 17th century England which exacerbated the situation and led to the English poor being particularly ‘dirty’.

Prior to 1642, Parliaments in England were temporary, appointed to advise the monarch for short periods. In 1642 the English Civil War broke out between the Roundheads (supporters of Parliament) and the Cavaliers (supporters of royalty). Wars are expensive and civil wars doubly so, so in 1643 the Parliamentarian, John Pym, introduced a series of taxes on staple items in order to raise funds for the war. One of the items taxed, along with beer, meat, salt, hats, tin, iron and wood, was soap. This tax on soap steadily raised the price of tax so that only the very wealthy could afford it. The king, Charles I, also granted a patent for soap (essentially producing a monopoly) to one small group of soap-makers. It was as a result of this use of patents to create monopolies that not long after laws were introduced restricting patents to new inventions only.

A few decades later, during the reign of Mary II and her Dutch husband, William of Orange, who ruled as joint sovereigns of England, the tax on soap was extended. Not only was soap taxed, but the production of soap was heavily controlled. Soap is relatively simple to make at home, even with very basic technologies, and so the only way that a tax on soap could work was if the government also controlled its production. Revenue officials ensured that soap was never produced in quantities smaller than one imperial ton and that soap-making equipment was locked up when not in use. It was illegal to produce soap for home use!

These laws and taxes lasted until 1853, meaning that for about 200 years soap was prohibitively expensive and illegal to make at home, severely limiting the hygiene of any but the very wealthy! So the peasants never really stood a chance and one can only imagine the disease and suffering that must have resulted from these harmful laws.

During September,

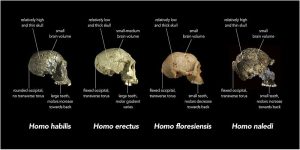

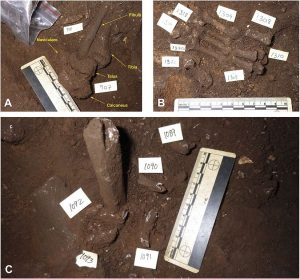

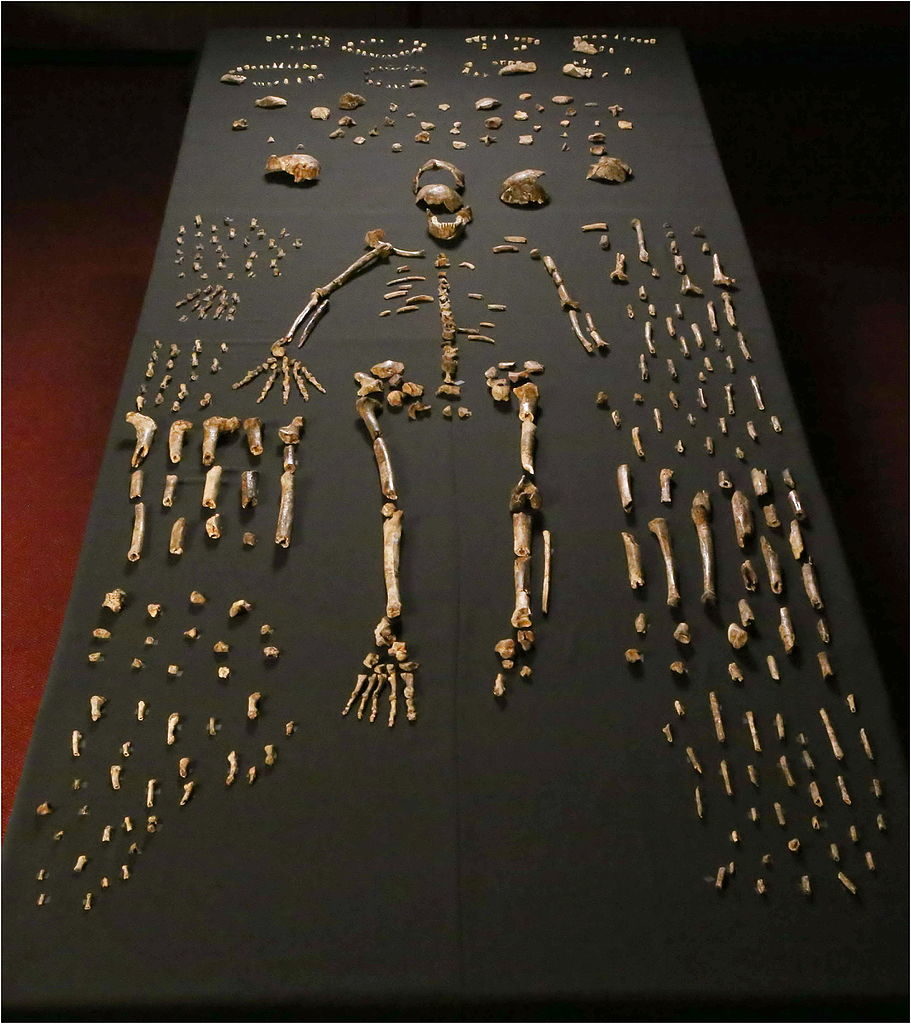

During September,  An interesting hominid was discovered in South Africa in 2014, named

An interesting hominid was discovered in South Africa in 2014, named  This year dates were

This year dates were

The second half of the year can be tough for younger students – they are often starting to get tired and attention may be flagging at this stage. In order to liven things up, the units for Foundation/Prep/Kindy (

The second half of the year can be tough for younger students – they are often starting to get tired and attention may be flagging at this stage. In order to liven things up, the units for Foundation/Prep/Kindy ( The older students have finished or are finishing off their

The older students have finished or are finishing off their  Students in Foundation/Prep/Kindy (

Students in Foundation/Prep/Kindy ( Older students are completing their main term research projects by finishing their

Older students are completing their main term research projects by finishing their  Our youngest students (

Our youngest students ( Students in integrated Year 3/4 classes (

Students in integrated Year 3/4 classes ( Each year level focuses on a different aspect of Australian history and enough topics are supplied to ensure that each student is working on new information, even in multi-age classes. Instead of finding a continual stream of new, novel HASS units, or repeating material some students have covered before, OpenSTEM’s

Each year level focuses on a different aspect of Australian history and enough topics are supplied to ensure that each student is working on new information, even in multi-age classes. Instead of finding a continual stream of new, novel HASS units, or repeating material some students have covered before, OpenSTEM’s

My grade 4 son's review is below. I think he liked seeing the patterns it made. It was just a…

Brad