Recently Amelia Earhart has been in the news once more, with publication of a paper by an American forensic anthropologist, Richard Jantz. Jantz has done an analysis of the measurements made of bones found in 1940 on the island of Nikumaroro Island in Kiribati. Unfortunately, the bones no longer survive, but they were analysed in 1941 by a doctor, D.W. Hoodless, from the Central Medical School in Fiji. Dr Hoodless concluded that the bones were of a stocky male, however, later researchers have argued about his conclusions. Jantz has examined a wide range of evidence, including photographs, measurements from Earhart’s clothing and the original measurements of the bones and has concluded that the bones are 84 times more likely to belong to Amelia Earhart than to any other person.

Let’s quickly recap the mystery surrounding Amelia Earhart:

Let’s quickly recap the mystery surrounding Amelia Earhart:

Earhart learned to fly in the early 1920s, taught by a pioneer female aviator, Anita Snook. Earhart worked at several jobs to save up for the tuition fees. She saved up again to buy a secondhand biplane. After Charles Lindburgh flew solo across the Atlantic in 1927, a female aviator, Amy Guest, unwilling to attempt the feat herself, offered to sponsor any woman prepared to try the Atlantic crossing. Earhart was part of a team of 3 who flew the Atlantic shortly after this and then completed the solo crossing herself in 1932. In 1937, Earhart was part of a team trying to fly around the world. Their first attempt ended when their aircraft had mechanical problems. The second attempt started on 1 June, 1937, leaving Miami, Florida and flying to South America, Africa, India and South-East Asia.

On 28 June, 1937, Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, set off from Darwin, Australia on the final leg of their voyage – crossing the Pacific. They had a brief stop in New Guinea on 29 June, before setting off for Howland Island in the Pacific – their next refuelling stop. It was planned that Earhart and Noonan would get radio directions to Howland Island from their support ship, the USCGC Itasca. However, the ship soon realised that although they could hear Earhart on the radio, she could not hear them. She was running low on fuel and was unable to see the island or the ship. The last clear broadcast said that she would run along a certain bearing. Later broadcasts were recieved but were faint and garbled and with many vessels now calling on that frequency it was no longer clear which signals were from Earhart. Sporadic signals continued for 4 or 5 days, but Earhart and Noonan were never found.

The search started almost immediately, with the Itasca searching the immediate area of Howland Island. A week later, US Navy planes flew over many of the surrounding islands, but didn’t find anything, although they did note signs of “recent habitation” on Gardner, now Nikumaroro, Island. The search was called off on 19 July, 1937. In 1938 Nikumaroro Island was settled and a skeleton of a woman, with “American” shoes was found, as well as the skull of a man. These bones had been disturbed and damaged by crabs. A cognac bottle with fresh water was found near the skeleton. Some of these bones were those analysed by the doctor in 1941.

Evidence such as the women’s shoes, a Benedictine liqueur bottle (which Earhart was known to have with her) and an American sextant, all found with the bones, suggest strongly that these remains are of Earhart and Noonan. Jantz’s research includes trying to reconstruct the likely size of Earhart’s bones to compare them with the 1941 measurements. It is therefore likely that Earhart and Noonan either crashed or landed close enough to Nikumaroro Island to be able to reach it, however, they were unfortunately not spotted by the Navy planes a week later.

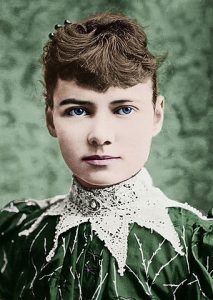

OpenSTEM® does not actually have a resource on Amelia Earhart (yet! Watch this space!), but we do have many other resources on fascinating Women Explorers, such as Nellie Bly, Isabella Bird, Gertrude Bell and Ida Pfeiffer. So if you’re keen to follow up on these topics with students, do have a look at some of these resources. As well as the interesting stories themselves, following their paths on maps and globes, can add enormously to the exploration of Geography curriculum material.

This week all of our students start to get into the focus areas of their units. For our youngest students that means starting to examine their “

This week all of our students start to get into the focus areas of their units. For our youngest students that means starting to examine their “ Students doing our stand-alone Foundation/Kindy/Prep unit (

Students doing our stand-alone Foundation/Kindy/Prep unit ( Students in Years 3 to 6 start their research projects this week. Students doing unit

Students in Years 3 to 6 start their research projects this week. Students doing unit  We continue publishing resources on explorers, a very diverse range from around the world and throughout time. Of course James Cook was an interesting person, but isn’t it great to also offer students an opportunity to investigate some other people that they hadn’t yet heard the name of? It is good to show the diversity and how it wasn’t just Europeans who explored.

We continue publishing resources on explorers, a very diverse range from around the world and throughout time. Of course James Cook was an interesting person, but isn’t it great to also offer students an opportunity to investigate some other people that they hadn’t yet heard the name of? It is good to show the diversity and how it wasn’t just Europeans who explored.

The kit was easy while still fun to build (except maybe for fitting the wires in). This was a fun…

Florence (15) and Keito (14), students at Hakusan International School