The end of the school year is fast approaching with the third term either over or about to end and the start of the fourth term looming ahead. There never seems to be enough time in the last term with making sure students have met all their learning outcomes for the year and with final reports to be prepared. The OpenSTEM® Understanding Our World® program takes the stress out of the fourth term as far as possible, ensuring that all curriculum items are covered well before the end of term and students are kept occupied with consolidation tasks so that teachers can prepare reports.

In units for Years 5 (Shaping Society, Working Together) and 6 (We Are One, But We Are Many), students have an assignment on a topic from Australian history and several of the suggested topics cover migrants to Australia, especially those from Asian countries. There is also a discussion about why people might become refugees, through factors such as war and natural disasters, or choose to migrate for a range of other reasons. Students in most year levels are examining cultural diversity and the make-up of Australian society.

In the news this week there is a story that has some relevance to these topics. Migrants and refugees from Asia make up a small but significant part of the numbers of people who come to Australia and find a home here, just as they have done since early colonial times. Many migrant and refugee women have experienced trauma and/or have come from countries where women’s place in society is very different than in our own. Some of these, just as in the rest of society, are single mothers or women at risk. However, they often face extra hurdles resulting from their history in their country of origin. For example, many women from Asian and African countries can not drive, either because they have not had the opportunity to learn, or it may even have been culturally inappropriate. The lack of a driver’s licence severely impacts their ability to get a job and transport themselves and their children to activities, including school and sports.

Access Community Services in Logan, south of Brisbane, has a Women at the Wheel program to help women prepare for a driving test. Currently there are women from Afghanistan, Burma and Somalia in the program and there is a very long waiting list for places. The program tries to match women with instructors who speak their native language to help them to understand the nuances of Australian road rules clearly. The women are delighted with the program, reporting that they find it very empowering and citing that having a driver’s licence will help them to find employment and transport themselves and their children as needed, making them independent and contributing members of the community.

In a way, these women finding a role for themselves in the community through learning to drive cars is almost reminiscent of the Afghan cameleers of the 19th century (shown above), who came to Australia to lead camel caravans, assisting explorers and taking the goods produced by farmers in isolated areas to market. Some of these people, from many places across the Asian subcontinent, chose to stay in Australia and adapted with the changing society, finding new roles for themselves and contributing to society in a range of ways, not least culturally and by enhancing the range of food and restaurant options available. The strength of Australia lies in the way that we pull together when times are tough and people need help. Aussies have always had a reputation for helping those in need and it is great to see this spirit continue today as people work together to build a better society.

Not strictly speaking within this week, but close enough to be included: it was 22 August, 1770, when James

Not strictly speaking within this week, but close enough to be included: it was 22 August, 1770, when James

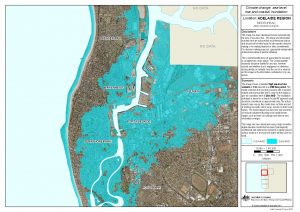

Global warming and sea level rise are related because a warmer global environment melts the ice at the poles and causes the sea level to rise. The same thing happened at the end of the

Global warming and sea level rise are related because a warmer global environment melts the ice at the poles and causes the sea level to rise. The same thing happened at the end of the  Scenario 1 has us take sudden, urgent action to reduce global warming and greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, as well as putting policies in place to control and reduce human impacts on the poles, and Antarctica in particular (reducing numbers of people in Antarctica, as well as their impact there). The situation 50 years from now (a time scale chosen to reflect the lifetimes of today’s children) has Antarctica enjoying a similar environment to today. The ozone hole has been repaired and the climate remains similar to that of the 20th century. The rate at which the ice has thinned has remained constant, instead of accelerating, and the acidification of the sea water has been kept low. The sea ice has decreased by “only” 12% and the ice on land by “only” 8%. Marine animals and birds show only small declines in population. Antarctica has been protected from invasive plants and animals through decreased human access and impact and maintenance of the harsh climate. Global air temperature has risen by less than 1 degree Celsius. Overall the sea level will rise by just under 1 metre, of which only 6cm comes from melting ice in West Antarctica.

Scenario 1 has us take sudden, urgent action to reduce global warming and greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, as well as putting policies in place to control and reduce human impacts on the poles, and Antarctica in particular (reducing numbers of people in Antarctica, as well as their impact there). The situation 50 years from now (a time scale chosen to reflect the lifetimes of today’s children) has Antarctica enjoying a similar environment to today. The ozone hole has been repaired and the climate remains similar to that of the 20th century. The rate at which the ice has thinned has remained constant, instead of accelerating, and the acidification of the sea water has been kept low. The sea ice has decreased by “only” 12% and the ice on land by “only” 8%. Marine animals and birds show only small declines in population. Antarctica has been protected from invasive plants and animals through decreased human access and impact and maintenance of the harsh climate. Global air temperature has risen by less than 1 degree Celsius. Overall the sea level will rise by just under 1 metre, of which only 6cm comes from melting ice in West Antarctica.

For many of us, the colder weather has started to arrive and mid-year assessment is in full swing. Teachers are under the pump to produce mid-year reports and grades. The OpenSTEM®

For many of us, the colder weather has started to arrive and mid-year assessment is in full swing. Teachers are under the pump to produce mid-year reports and grades. The OpenSTEM®  Students in year levels from Foundation (Kindy/Prep) to Year 3 work through curriculum-aligned sections of work throughout the term and are assessed through a variety of interactions, which include students’ verbal and written responses, as well as drawings and craft projects completed as part of the term work. Students in Years 4 to 6 usually have one main project or summative assessment piece for the term. However, the student workbook provided with each unit is structured to step students through the formative process of completing this work over several weeks, allowing teachers to keep track of their progress and provide regular feedback. The assessment guide provided with each unit, guides teachers on how to assess the assessment piece (as well as the rest of the term work, including the student workbook), as well as providing a marking rubric and vocabularies for students’ achievements from A to E.

Students in year levels from Foundation (Kindy/Prep) to Year 3 work through curriculum-aligned sections of work throughout the term and are assessed through a variety of interactions, which include students’ verbal and written responses, as well as drawings and craft projects completed as part of the term work. Students in Years 4 to 6 usually have one main project or summative assessment piece for the term. However, the student workbook provided with each unit is structured to step students through the formative process of completing this work over several weeks, allowing teachers to keep track of their progress and provide regular feedback. The assessment guide provided with each unit, guides teachers on how to assess the assessment piece (as well as the rest of the term work, including the student workbook), as well as providing a marking rubric and vocabularies for students’ achievements from A to E. Continuous assessment is widely recognised internationally as promoting “inclusive and equitable quality education”. A

Continuous assessment is widely recognised internationally as promoting “inclusive and equitable quality education”. A  The authors of the UNESCO report warn that “high-stakes, large-scale, annual and multi-annual instruments” of assessment “threatens education” and “continues to favour information over knowledge, and mechanical skill over practical application”. Continuous assessment is also in line with the suggestions in the

The authors of the UNESCO report warn that “high-stakes, large-scale, annual and multi-annual instruments” of assessment “threatens education” and “continues to favour information over knowledge, and mechanical skill over practical application”. Continuous assessment is also in line with the suggestions in the

My 9 year old son fell in love with all the aspects of this little robotic guy - the simple…

Cara, Parent